Back in the 1920s there was an oft-repeated joke about the British thriller writer Edgar Wallace. A friend was said to have telephoned him one day, only to be told that Wallace was writing a new novel. “That’s okay,” the caller remarked, “I’ll wait.”

Back in the 1920s there was an oft-repeated joke about the British thriller writer Edgar Wallace. A friend was said to have telephoned him one day, only to be told that Wallace was writing a new novel. “That’s okay,” the caller remarked, “I’ll wait.”

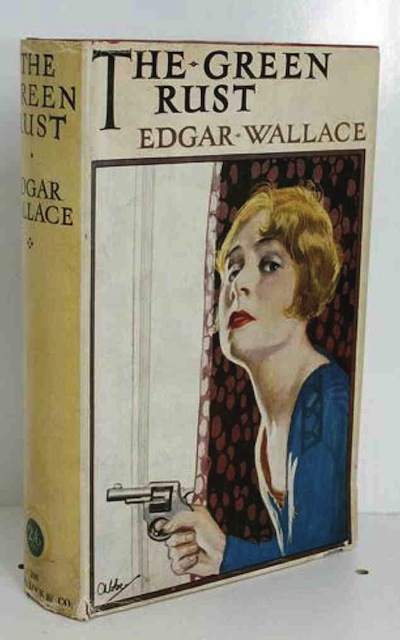

One of the most popular writers of the early 20th century, and certainly one of the most prolific, Edgar Wallace turned out an astonishing 130 novels (18 alone in 1926), 40 short story collections, 25 plays, some 15 nonfiction books, plus journalism, criticism, poetry, and columns, in a little over 30 years. During his peak it was claimed that one-quarter of all the books read in England were penned by Wallace, and he remains one of the most filmed authors of all time. Yet today he hovers like a ghost over the mystery genre, his name often invoked, but his books seldom read.

The man whose name would become a synonym for crime fiction was born in the London suburb of Greenwich in 1875, the product of a one-night stand between two actors. His mother placed him with a foster family when he was a week old. Called Richard Horatio Edgar Freeman in his youth, he enjoyed a happy childhood and was something of an extrovert, though from an early age he demonstrated a habit of withdrawing and running away from any problems he encountered rather than dealing with them. As a young man he worked a host of different jobs before joining the Army and ending up in South Africa. Upon finding he had little taste for soldiering, he bought his way out, eventually returning to London, where he became a crime reporter. It was then that he adopted “Edgar Wallace” as his byline, borrowing his new last name from General Lew Wallace, the author of Ben-Hur.

The man whose name would become a synonym for crime fiction was born in the London suburb of Greenwich in 1875, the product of a one-night stand between two actors. His mother placed him with a foster family when he was a week old. Called Richard Horatio Edgar Freeman in his youth, he enjoyed a happy childhood and was something of an extrovert, though from an early age he demonstrated a habit of withdrawing and running away from any problems he encountered rather than dealing with them. As a young man he worked a host of different jobs before joining the Army and ending up in South Africa. Upon finding he had little taste for soldiering, he bought his way out, eventually returning to London, where he became a crime reporter. It was then that he adopted “Edgar Wallace” as his byline, borrowing his new last name from General Lew Wallace, the author of Ben-Hur.

The first few years of the 20th century would prove to be a challenge for Wallace, who by then had married and had a child, but who habitually lived beyond his means. It was said that he believed any attempt at thrift was a bad omen, implying that his fortunes might someday diminish. In 1902 he went back to South Africa, this time to take a job as a newspaper editor, but, while there, his baby daughter Eleanor became ill and died. Devastated, Wallace and his wife Ivy escaped back to London, but before long he was approached by his birth mother who, because of his growing renown, believed him to be wealthy. Already overwhelmed by the weight of his personal problems, Wallace sent his impoverished mother away with a pittance, an act that would fill him with guilt in later years.

In 1904 Wallace was engaged to cover the Russo-Japanese War for the papers and relocated to Europe. There he met a group of spies, which gave him the idea for his first mystery novel, The Four Just Men, which was published in 1905. The first of Wallace’s “secret organization” stories, it chronicled the actions of a quartet of wealthy vigilantes who combat what they perceive to be unpunishable wrongs through assassination. His decision to publish and promote the novel himself, though, proved financially disastrous and forced him to declare bankruptcy.

With nowhere to go but up, he began turning out book after book, scoring his first real success with 1911’s Sanders of the River, an adventure novel based on his time in Africa. More African novels followed, as well as more Just Men adventures, plus a series featuring Inspector Elk of Scotland Yard. After divorcing Ivy in 1918, he threw himself into his writing, producing over the next decade scores of crime thrillers (even a second marriage in 1921, to his former secretary, did little to slow his pace).

With nowhere to go but up, he began turning out book after book, scoring his first real success with 1911’s Sanders of the River, an adventure novel based on his time in Africa. More African novels followed, as well as more Just Men adventures, plus a series featuring Inspector Elk of Scotland Yard. After divorcing Ivy in 1918, he threw himself into his writing, producing over the next decade scores of crime thrillers (even a second marriage in 1921, to his former secretary, did little to slow his pace).

The fictional world of Edgar Wallace is populated with colorfully named criminal organizations—the “Fellowship of the Frog,” the “Red Hand,” and the “Crimson Circle,” to name a few—supervillains, outwardly respectable men with secret lives, intrepid young amateur sleuths (often reporters), plucky heroines, and assorted hoods, crooks, and gangsters. He was also one of the first to feature a policeman as the protagonist in a story, as opposed to an amateur sleuth. His narrative style is at once breathless, conversational, and melodramatic, while he frequently confides in the reader.

He could be playful as well. The 1928 adventure The Feathered Serpent opens with the following bit of self-satire:

What annoyed Peter Dewin most, as it would have annoyed any properly constituted reporter, was what he called the mystery-novel element in the Lane case.

A really good crime story may gain in value from a touch of the bizarre, but all good newspapermen stop and shiver at the mention of murder gangs and secret societies, because such things do not belong to honest reporting, but are the inventions of writers of best or worst sellers.

Wallace’s work ethic and concentration while writing remain legendary. He kept the plot of each book entirely in his head, never making notes, and worked very long hours, all the while chain smoking cigarettes through a dramatically long holder, and downing cup after cup of sugared tea. He habitually wrote the first page of each book in longhand, and then dictated the rest either to a secretary or into a machine.

Wallace’s work ethic and concentration while writing remain legendary. He kept the plot of each book entirely in his head, never making notes, and worked very long hours, all the while chain smoking cigarettes through a dramatically long holder, and downing cup after cup of sugared tea. He habitually wrote the first page of each book in longhand, and then dictated the rest either to a secretary or into a machine.

In 1924, he introduced his most resonant series character, John G. Reeder, in the novel Room 13. A former Scotland Yard man, Reeder worked in the Public Prosecutor’s office, but was called upon by the Yard to solve unfathomable cases, most often bank heists. Middle-aged, unfashionably dressed, and timid of character, he possessed a keen, wily intellect whose ability to understand the criminal element actually makes him nervous. “I see wrong in everything,” he confesses in The Mind of J.G. Reeder (1925). “That is my perversion—I have a criminal mind!” Reeder’s adventures were chronicled in three novels and two story collections.

While Wallace’s works had been sources for films as early as 1915, he started writing directly for the movies in the late 1920s. He was lured to Hollywood in 1931, where his most notable script would be for King Kong. He also contributed the screenplay to the 1932 version of Hound of the Baskervilles, which was produced in England. But his roller-coaster life was facing its final turn. Already suffering from diabetes (exacerbated by his passion for sugary tea), he contracted double pneumonia and died in Beverly Hills in 1932, at the relatively young age of 56.

Over 50 films based on Edgar Wallace stories were filmed in the UK between 1925 and 1939 alone, most enjoyably the flamboyantly sensational The Dark Eyes of London (1939; dir: Walter Summers) starring Bela Lugosi as the villain and Greta Gynt as the lady in distress. It was colorized and re-released after WWII as The Human Monster.

Over 50 films based on Edgar Wallace stories were filmed in the UK between 1925 and 1939 alone, most enjoyably the flamboyantly sensational The Dark Eyes of London (1939; dir: Walter Summers) starring Bela Lugosi as the villain and Greta Gynt as the lady in distress. It was colorized and re-released after WWII as The Human Monster.

How is it that a writer once considered to be second in popularity only to Dickens, whose face once adorned the cover of Time magazine, became a memory so quickly after his death? Possibly because Wallace’s output was so enormous that it was hard for any one work, even any one series, to achieve classic status. Also, unlike his contemporaries Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, and Edgar Rice Burroughs, he never created a truly iconic character. It was the name Edgar Wallace that sold the books, not a particular title or character, and once the real Edgar Wallace was gone, his readers moved on and his works fell out of print. But beginning in the late 1950s, Wallace’s name enjoyed a posthumous renaissance in Germany, where film adaptations of his thrillers became a cottage industry. In 1969, Wallace’s daughter Penelope (by his second marriage) formed The Edgar Wallace Society in order to promote his legacy.

Today, thanks to the ebook and download revolution, his works are easier to find than at any time over the past 40 years, and anyone today wishing to connect the legendary name with the master storytelling talent behind it would do well to pick up an Edgar Wallace thriller. There, one will discover that the public’s appetite for gripping, bizarre, thrilling adventures involving supervillains with mad schemes was being satisfied long before the creation of a fellow named James Bond.

Today, thanks to the ebook and download revolution, his works are easier to find than at any time over the past 40 years, and anyone today wishing to connect the legendary name with the master storytelling talent behind it would do well to pick up an Edgar Wallace thriller. There, one will discover that the public’s appetite for gripping, bizarre, thrilling adventures involving supervillains with mad schemes was being satisfied long before the creation of a fellow named James Bond.

THE ALL-TOO-POSSIBLE CRIME

In 1905, Edgar Wallace self-published his novel The Four Just Men. As a publicity gimmick he kept back the solution to the mystery and offered a cash prize to anyone who could solve it. The book sold tremendously well and helped set off a craze for detective fiction. Unfortunately for the author, though, the plot wasn’t as impenetrable as he thought—reducing him to bankruptcy. Undaunted, the flamboyant Wallace wrote on—and eventually became one of the most successful writers of his era.

This article first appeared in Mystery Scene Summer Issue #130.