Fletch Lives

Fletch Lives

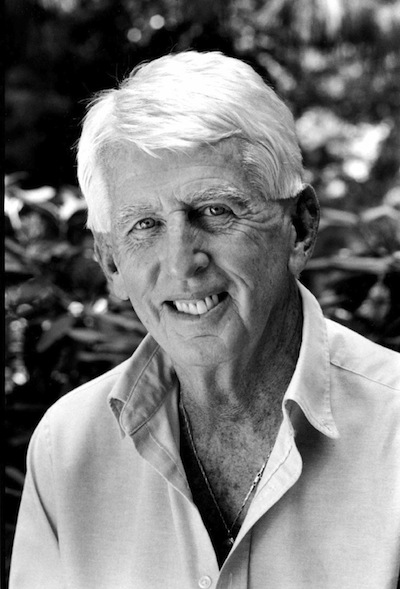

Gregory Mcdonald, 1937-2008. Photo: Nancy Crampton.

It’s not Gregory Mcdonald’s epitaph, but it may as well be. Mcdonald wrote 26 published books over the course of a decades-long career, yet when he died last September at the age of 71, tribute after tribute turned not only to the same novel but the same excerpt to illustrate his considerable gifts as a storyteller.

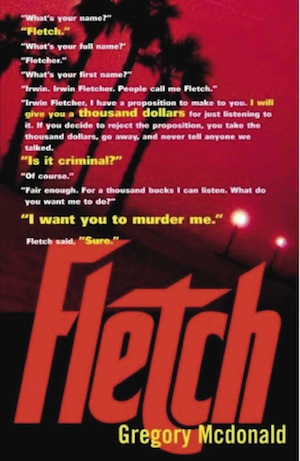

It was a fitting choice for a fond farewell, as the passage had been, years before, an introduction—a bold fanfare that announced to the mystery world that someone important had just arrived on the scene. Two someones, actually: Mcdonald and a new kind of sleuth.

But why not let those words speak for themselves?

“What’s your name?”

“Fletch.”

“What’s your full name?”

“Fletcher.”

“What’s your first name?”

“Irwin.”

“What?”

“Irwin. Irwin Fletcher. People call me Fletch.”

“Irwin Fletcher, I have a proposition to make to you. I will give you a thousand dollars for just listening to it. If you decide to reject the proposition, you take the thousand dollars, go away, and never tell anyone we talked. Fair enough?”

“Is it criminal? I mean, what you want me to do?”

“Of course.”

“Fair enough. For a thousand bucks I can listen. What do you want me to do?”

“I want you to murder me.”

Even readers who never picked it up themselves can guess the novel that begins with those punchy, pithy lines. It’s Fletch, of course.

And those readers who haven’t read the book? I can’t believe, after reading that opening, that they’re not running straight to the nearest bookstore to look for a copy. To my mind, it’s one of the great openings of the mystery genre: so compact, almost spare, yet full of intrigue, wit and promise. If people keep reading Mcdonald in the decades to come—and I believe they will—those 101 words will have a lot to do with it.

In fact, I know how sharp Fletch’s opening hook is from personal experience. I first encountered Mcdonald’s Fletch mysteries under what I’d call the ideal circumstances: I was on vacation with my wife and in-laws, and it was raining...and raining...and raining. After finishing the book I’d brought with me and growing absolutely sick of Scrabble and Rummikub, I started hunting for something else to do. Fortunately, the beach house we were renting had bookshelves lined with old paperbacks.

I remember seeing The Amityville Horror, The Ghost of Flight 401, a lot of Michael Crichton, a lot of James Michener.

And then—cue the “Hallelujah” chorus—lots and lots of Gregory Mcdonald.

Though Mcdonald’s Fletch mysteries were hugely popular throughout the 1970s and ’80s, with tens of millions of copies in print, I somehow managed to miss the hullabaloo. All I knew were the two Fletch movies starring Chevy Chase. And, by another stroke of luck, I’d only seen the first, which ain’t too shabby. (The 1989 sequel, Fletch Lives? Shabby.)

Though Mcdonald’s Fletch mysteries were hugely popular throughout the 1970s and ’80s, with tens of millions of copies in print, I somehow managed to miss the hullabaloo. All I knew were the two Fletch movies starring Chevy Chase. And, by another stroke of luck, I’d only seen the first, which ain’t too shabby. (The 1989 sequel, Fletch Lives? Shabby.)

So I slid Fletch off the shelf, glanced at those killer opening lines...and didn’t stop reading until I ran out of sequels two days later. Somewhere in there, it stopped raining, but I barely even noticed.

The books I zoomed through—the first six of Mcdonald’s nine Fletch novels—were lean but not slight, fast-paced but not frenzied, and comical but not cartoonish, all with mysteries that managed to be satisfyingly complex yet not convoluted.

And there was more to them than just good stories well told (though they certainly were that). Yes, these were traditional mysteries in the sense that crimes were committed, clues accumulated, and culprits caught. Yet the approach didn’t feel traditional at all.

There was a spartan style, whole chapters whipping by with nothing but sharp, often hilarious dialogue pushing the plot forward.

There was a unique, slightly askew world view, rebellious, sly, sometimes absurdist, with flashes of tenderhearted compassion.

And, most of all, there was a unique hero.

Of course, when the first Fletch novel was published in 1974, there’d already been mysteries that didn’t star private eyes or cops or snoopy old ladies. There’d even been some that starred (as does Fletch) a journalist. But none featured a journalist hero who was so, shall we say, ethically flexible.

Lies. Masquerades. Sex. Fletch used them all, when they suited his purposes. And he wasn’t above some wicked trickery when it came to evading his alimony-hunting ex-wives, too. Yet he had an idiosyncratic code of honor, as well: Though he won the Bronze Star while serving as a Marine, he refused to accept the award for reasons known only to himself.

Imagine that. A decorated war hero protagonist who wasn’t portrayed as an unstoppable killing machine. No, Fletch was a lover (and liar), not a fighter.

“The only question resolved by violence is who is the stronger—not the height of intelligence, interest or value,” Mcdonald said to Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine columnist J. Rentilly in a rare interview shortly before his death. “A violent resolution mostly impedes understanding.”

Not that Fletch was some kind of hippie—though he did have an aversion to authority figures and (in his first adventure, at least) wearing shoes. But his cynicism and air of sardonic detachment were certainly symptomatic of the late ’60s/early ’70s zeitgeist that birthed him.

Just call him Cool Hand Fletch.

Over the years, Mcdonald launched several other, less successful series, all of them starring charming rogues who doggedly sniff out the truth without resorting to violence or macho bluster. “Sunlight mysteries,” a critic once dubbed them, and Mcdonald told Rentilly he was proud to think of himself as a master of the form.

Yet Mcdonald’s writing wasn’t all sunshine and light. His first published novel, Running Scared (1964), is about a college student who refuses to intervene when his roommate commits suicide. A later book, The Brave (1991), is a grim look at a down-on-his-luck Native American who agrees to sacrifice himself in a snuff film. And in the mid-1980s, Mcdonald abandoned the still-popular Fletch series to focus on a proposed “quartet” of philosophically minded literary novels. (Only three were published, and Mcdonald returned to writing mysteries with the Fletch spin-off Son of Fletch in 1993.)

In fact, though he was a two-time Edgar winner and a former president of the Mystery Writers of America, Mcdonald seemed to feel ambivalent about the genre that made him rich and famous.

In fact, though he was a two-time Edgar winner and a former president of the Mystery Writers of America, Mcdonald seemed to feel ambivalent about the genre that made him rich and famous.

“I think the mystery may be the greatest form for social criticism,” his official website quotes him as saying, “simply because it is pedestrian.”

High praise...or backhanded compliment?

Like his greatest creation, it seems, Mcdonald didn’t like to be pinned down.

Born and raised in New England, Mcdonald put himself through Harvard sailing and servicing yachts for East Coast blue bloods. He started writing young, working out a draft of what would become his 1988 literary novel Exits and Entrances at the age of 16 and publishing Running Scared when he was only 27. His first novel met with a mixed reception, however, and he made his living as a Boston Globe reporter and editor until the instant success of Fletch gave him the freedom to quit.

Yet he never enjoyed life as a jet-setting, best-selling publishing superstar. According to The New York Times, if a fellow airplane passenger asked he what he did for a living, he’d say he sold insurance—thus guaranteeing a quick end to the conversation. Mcdonald also complained in interviews about bookstore mob scenes and grabby female fans.

Eventually, he moved to a Tennessee farm, stopped making public appearances, and developed a reputation (in the publishing world, at least) as a recluse. When he died of prostate cancer last fall, fans hadn’t seen a new novel from him in nine years.

The man who’d won fame and fortune for beginning things with a bang had gone out very, very quietly.

Not that Mcdonald’s story is over. A Fletch film franchise reboot has been in the works for nearly a decade, with top Hollywood writers like Clerks auteur Kevin Smith and Scrubs creator Bill Lawrence hailing the original books as an early inspiration. And Vintage has been keeping not just the Fletch novels but also Mcdonald’s Son of Fletch and Flynn series in print, hopefully drawing new fans to the author’s “sunshine mysteries.”

And then there’s what I think is the best cause for hope of all: Fletch itself. And that opening.

Years after stumbling across it on that fortuitously rainy day, I reread it. Mcdonald had just passed away, and it seemed like the right time to revisit my old friend Fletch.

And wouldn’t you know it, I couldn’t stop at 101 words. I couldn’t stop at one page. I had to reread the whole book. And then the next and then the next. And I don’t think I’ll be the only one who still finds that old hook as sharp as ever. The movie may have stunk, but the sentiment holds true: Fletch lives.

A GREGORY MCDONALD SELECTED READING LIST

Fletch Novels

Fletch, 1974

Confess, Fletch, 1976

Fletch's Fortune, 1978

Fletch and the Widow Bradley, 1981

Fletch's Moxie, 1982

Fletch and the Man Who, 1983

Carioca Fletch, 1984

Fletch Won, 1985

Fletch, Too, 1986

Flynn Novels

Flynn, 1977

The Buck Passes Flynn, 1981

Flynn's In, 1984

Flynn's World, 2003

Son of Fletch Novels

Son of Fletch, 1993

Fletch Reflected, 1994

Skylar Novels

Skylar, 1995

Skylar in Yankeeland, 1997

Steve Hockensmith is the author of the “Holmes on the Range” historical mysteries. The latest book is Dear Mr. Holmes: Seven Holmes on the Range Mysteries.

This article first appeared in Mystery Scene Winter Issue #108.