Read today, The Penguin Pool Murder is not only a fascinating snapshot of New York City immediately after the 1929 stock market crash, it is a remarkable document of an author’s on-the-job training.

Read today, The Penguin Pool Murder is not only a fascinating snapshot of New York City immediately after the 1929 stock market crash, it is a remarkable document of an author’s on-the-job training.

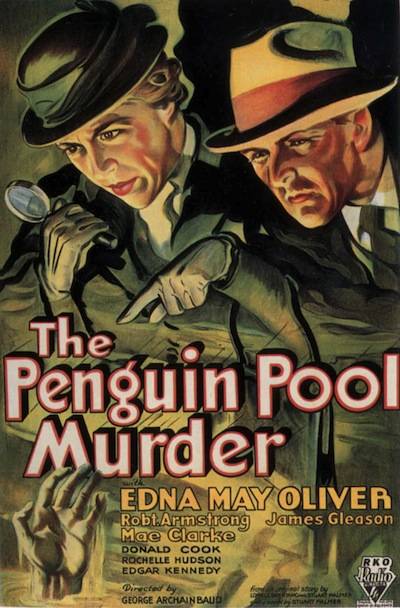

A movie poster from the 1932 film adaptation of The Penguin Pool Murder.

Half a century before Jessica Fletcher snooped her way to celebrity on Murder, She Wrote, there was another fictional schoolteacher-turned-sleuth who had a talent for tripping over bodies: Hildegarde Withers. The tall and bony, fortyish, umbrella-toting spinster was a staid fixture at Manhattan’s Jefferson School before stumbling into her true calling as an amateur sleuth. Along with her good friend (and, briefly, fiancé) Inspector Oscar Piper, who labeled her “God’s gift horse to all dumb cops,” she developed a penchant for cutting through incredibly complex puzzles with a combination of diligent questioning, attention to details, and an unwillingness to let Piper settle for the easiest, most convenient, most politically expedient answer.

Hildegarde Martha Winters was the creation of Stuart Palmer (1905–1968), a reporter turned novelist who would go on to make his name as a screenwriter. Proudly old-fashioned, she is popular with her third-grade students, with whom she tries to be stern, but her affection for them usually shows through. When it comes to adults, however, she suffers no fools, yet through it all remains a closet romantic. Hildegarde often uses her teacherly wiles in investigations, stating: “I’ve taught school long enough to know when anybody is telling the truth or not.” During interrogations she keeps notes in shorthand for her and Piper’s later use, and she often makes detailed sketches of the crime scene (more for the benefit of the reader than anyone else).

In her debut novel, 1931’s The Penguin Pool Murder, she is thrust into the action by way of discovering a body floating in the penguin tank of the New York Aquarium, where she has taken her class. Once she has been drafted into the investigation, she confesses to Piper, who works in the city’s homicide division, “It is the ambition of my life to play detective.” With that declaration was launched the most disarming and delightful relationship between a law enforcement official and a wily, brash amateur this side of John Steed and Emma Peel.

Read today, The Penguin Pool Murder is not only a fascinating snapshot of New York City immediately after the 1929 stock market crash (which is a key plot point, in fact), it is a remarkable document of an author’s on-the-job training. Chapter by chapter, Palmer’s initially purple, dialogue-heavy prose smoothes out and the story solidifies as it goes along, before toughening like cooling steel for the climax. An odd mix of cozy and hardboiled styles, Penguin Pool’s characters also waver a bit in their particulars. When Hildegard is first introduced, for instance, she is said to have been born in Boston; later when it becomes important to the story that she hail from Dubuque, Iowa, she suddenly does, with no explanation for the discrepancy.

The Penguin Pool Murder was successful enough for Hollywood to take notice, and the film adaptation, starring Edna May Oliver as Hildegarde and James Gleason as Piper, was released in 1932. Stuart Palmer was so delighted with the casting that he actually began tailoring novels to follow suit! In subsequent books Hildegarde became somewhat older and started being characterized as equine in order to conform to Miss Oliver’s good-natured description of herself as “horse-faced.” Meanwhile, the cigar-chomping Inspector Piper, whom Hildegarde calls “young man” throughout the first book, was recast as an older and flintier career copper to more resemble the middle-aged bantam image established by Gleason. Ironically, while the literary Hildegard remained in the image of Edna May Oliver, in subsequent films the actress was replaced, first by Helen Broderick and then by ZaSu Pitts, neither of whom quite captured the character.

The Penguin Pool Murder was successful enough for Hollywood to take notice, and the film adaptation, starring Edna May Oliver as Hildegarde and James Gleason as Piper, was released in 1932. Stuart Palmer was so delighted with the casting that he actually began tailoring novels to follow suit! In subsequent books Hildegarde became somewhat older and started being characterized as equine in order to conform to Miss Oliver’s good-natured description of herself as “horse-faced.” Meanwhile, the cigar-chomping Inspector Piper, whom Hildegarde calls “young man” throughout the first book, was recast as an older and flintier career copper to more resemble the middle-aged bantam image established by Gleason. Ironically, while the literary Hildegard remained in the image of Edna May Oliver, in subsequent films the actress was replaced, first by Helen Broderick and then by ZaSu Pitts, neither of whom quite captured the character.

The 1930s were an incredibly productive period for Palmer, who followed up The Penguin Pool Murder with Murder on Wheels (1932), in which it is revealed that Oscar and Hildegarde reconsidered their earlier decision to run off to City Hall and get hitched; Murder on the Blackboard (1932); The Puzzle of the Pepper Tree (1933); The Puzzle of the Silver Persian (1934); The Puzzle of the Red Stallion (1935); and The Puzzle of the Blue Banderilla (1937). At the same time Palmer was turning out Hildegarde Withers short stories, many for the magazine Mystery, which was sold exclusively in Woolworth’s stores. All of the Withers novels and stories feature complicated plots and contain a wealth of Manhattanisms and time-capsule references to such luminaries as Boss Tweed, Herbert Hoover, even Adolf Hitler. The author’s sense of product placement, meanwhile, would go unrivaled until the advent of Stephen King.

Having turned his attention to scripting movies by the late 1930s, Stuart Palmer had far less time for writing novels. That, in addition to Palmer’s growing, chronic case of writer’s block, meant that only seven more Hildegard Withers books appeared over the next two decades. The Puzzle of the Happy Hooligan came out in 1941, followed by Miss Withers Regrets (1947); the short story collection The Riddles of Hildegarde Withers (1947); Four Lost Ladies (1949); The Green Ace (1950); Nipped in the Bud (1951); and Cold Poison (1954).

Beginning in 1950, Palmer embarked on an unprecedented collaboration with prolific author Craig Rice (real name: Georgiana Craig) to combine Hildegarde Withers with Rice’s character, the boozy Chicago mouthpiece John J. Malone, in a series of stories that appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Never before had two completely different established characters from different living authors teamed up for a new series. These stories were eventually collected in the 1963 volume People vs. Withers and Malone, and one of them, “Once Upon a Train,” became the basis for the 1950 film Mrs. O’Malley and Mr. Malone, only without Hildegarde. Malone’s female foil in the film was Hattie O’Malley, played by Marjorie Main at her most obstreperous.

Hildegarde Withers stories continued to appear in the pages of EQMM well into the 1960s, but by then time was running out for Stuart Palmer. An inveterate cigar smoker, the onetime MWA president contracted cancer of the larynx, which led to his death in 1968. He left an unfinished Hildegarde Withers novel, which was completed by Fletcher Flora, who was one of the regular ghostwriters of the Ellery Queen byline. Published in 1969, Hildegarde Withers Makes the Scene finds a retired, but rather hip, Hildegarde living in California and getting involved in the case of a missing flower child, which eventually leads to a murder. Putting Miss Withers into the hippie culture of Haight-Ashbury sounds like a gimmick, but it works remarkably well, thanks to Palmer’s sensitivity toward and understanding of the 1960s youth culture, and instilling the same in his sleuth. In 1972 the book was adapted for a television movie titled A Very Missing Person, starring Eve Arden as Hildegarde and James Gregory as Piper.

Hildegarde Withers has sometimes been referred to as “the American Miss Marple,” but the resemblance is purely superficial. While both are spinsters, Miss Marple seems to have been born elderly, whereas Hildegarde was only 39 in Penguin Pool (though to the 25-year-old author, that may have seemed old). The sharp-tongued Miss Withers is a keen and proactive detective who thrives on the hunt for clues, whereas the gossipy Miss Marple processes information through her own experiences and knowledge of people to come up with solutions. What’s more, Jane Marple never seems to have held a job, whereas generations of New York schoolchildren learnt under the steely gaze of Hildegarde Withers—a few were even drafted to be her Baker Street Irregular-style assistants.

Hildegarde Withers has sometimes been referred to as “the American Miss Marple,” but the resemblance is purely superficial. While both are spinsters, Miss Marple seems to have been born elderly, whereas Hildegarde was only 39 in Penguin Pool (though to the 25-year-old author, that may have seemed old). The sharp-tongued Miss Withers is a keen and proactive detective who thrives on the hunt for clues, whereas the gossipy Miss Marple processes information through her own experiences and knowledge of people to come up with solutions. What’s more, Jane Marple never seems to have held a job, whereas generations of New York schoolchildren learnt under the steely gaze of Hildegarde Withers—a few were even drafted to be her Baker Street Irregular-style assistants.

The remarkable thing about the Hildegarde Withers books is that, despite the fact that they are in and of the time in which they were written, they do not date. If anything, they present a wonderful window into the ongoing decades, anchored by a constant lead character, not unlike Michael McDowell’s Jack and Susan series written in the 1980s, but set in successive decades. More pertinently, they are finely tuned, challenging puzzle stories that feature a delightful, witty protagonist whom some of us would have vastly preferred to our real third-grade teachers.

The Hildegarde Withers Mysteries

The Penguin Pool Murder (1931)

Murder on the Blackboard (1932)

Murder on Wheels (1932)

The Puzzle of the Pepper Tree (1933)

The Puzzle of the Silver Persian (1934)

The Puzzle of the Red Stallion (1936)

The Puzzle of the Blue Banderilla (1937)

The Puzzle of the Happy Hooligan (1941)

Miss Withers Regrets (1947)

The Riddles of Hildegarde Withers (1947, ss)

Four Lost Ladies (1949)

The Green Ace (1950)

The Monkey Murder (1950, ss)

Nipped in the Bud (1951)

Cold Poison (1954)

The People vs. Withers and Malone, written with Craig Rice (1963, ss)

Hildegarde Withers Makes the Scene, completed by Fletcher Flora (1969)

This article first appeared in Mystery Scene Spring Issue #119.