Allan Pinkerton and the plot to assassinate Abraham Lincoln

Allan Pinkerton and the plot to assassinate Abraham Lincoln

Allan Pinkerton and President Abraham Lincoln, shortly after the Battle of Antietam on October 3, 1862. Before he became head of the Union Intelligence Services, Pinkerton foiled an assassination attempt against the President-elect. Photo: Library of Congress.

The PTA meeting is over and I’m standing at the punch bowl, minding my own business. A guy in a Nationals baseball cap comes up, looking angry. He leans in close and jabs a finger in my chest. “You’re the guy who’s writing the book about Allan Pinkerton,” he says. “Let me tell you something about Allan Pinkerton. Allan Pinkerton bashed my grandfather over the head with a club at Homestead—cracked his skull right open. Is that in your book, Mr. Author?”

This happens more often than you might think. I’ve just written a nonfiction book called The Hour of Peril, about Pinkerton, the founder of the legendary Pinkerton Detective Agency, and one of the most controversial episodes of his storied career. It’s set in 1861, just after the election of Abraham Lincoln, and just before the Civil War broke out. It was an especially turbulent moment in American history, and over a period of 13 days, as Lincoln traveled by train from Springfield, Illinois, to Washington, D.C., for his inauguration, the air was filled with rumors of an assassination plot. In Maryland, where Lincoln’s train would cross below the Mason-Dixon line for the first time, there were whispers that he would be shot—or stabbed, or that his train would be blown up—at a whistle-stop appearance in Baltimore. Pinkerton, America’s top lawman, caught wind of the plot and began racing the clock to uncover hard evidence, in the hope of persuading Lincoln to take action before time ran out.

The broad strokes of the Baltimore Plot, as this episode came to be known, are well known, but very few people know the story behind the story, and that story begins with Pinkerton. He was a tough nut—scrappy, grizzled, quick to anger. He was born in Scotland, he got into trouble with the law, and he came to America as a barrel-maker. One day he was out cutting wood for his barrels and stumbled across a group of counterfeiters dividing their ill-gotten spoils around a campfire. The following day he led the local sheriff on a raid and rounded them up. The next thing you know, Pinkerton is a lawman, and soon after that he became something entirely new—a private detective. His logo was a stern, unblinking eye, glaring out above the words “We Never Sleep.” Soon that logo brought a new phrase to the American lexicon—private eye.

The broad strokes of the Baltimore Plot, as this episode came to be known, are well known, but very few people know the story behind the story, and that story begins with Pinkerton. He was a tough nut—scrappy, grizzled, quick to anger. He was born in Scotland, he got into trouble with the law, and he came to America as a barrel-maker. One day he was out cutting wood for his barrels and stumbled across a group of counterfeiters dividing their ill-gotten spoils around a campfire. The following day he led the local sheriff on a raid and rounded them up. The next thing you know, Pinkerton is a lawman, and soon after that he became something entirely new—a private detective. His logo was a stern, unblinking eye, glaring out above the words “We Never Sleep.” Soon that logo brought a new phrase to the American lexicon—private eye.

We think of Pinkerton detectives as hard men with big fists and blazing guns. Remember that relentless posse of lawmen chasing Butch and Sundance? They were Pinkertons. The guys shooting back at the train robbers from inside the freight car? They were Pinkertons. The guys knocking heads together during the strike at the steel mill? Those were Pinkertons, too, sad to say.

This last thing—the union busting—is what led to my showdown at the punch bowl. I knew exactly what had the guy so worked up. He was talking about the Homestead Strike of 1892, a truly horrific clash between striking steel workers and Pinkerton men in Pennsylvania. This was a terrible, bloody episode, with plenty of blame on both sides, but I can tell you, for sure, that Allan Pinkerton didn’t crack anybody’s grandfather over the head that day. Why? Because he was dead. He died eight years earlier.

This last thing—the union busting—is what led to my showdown at the punch bowl. I knew exactly what had the guy so worked up. He was talking about the Homestead Strike of 1892, a truly horrific clash between striking steel workers and Pinkerton men in Pennsylvania. This was a terrible, bloody episode, with plenty of blame on both sides, but I can tell you, for sure, that Allan Pinkerton didn’t crack anybody’s grandfather over the head that day. Why? Because he was dead. He died eight years earlier.

This information seemed to appease my finger-jabbing friend, but just barely. He clearly felt that I’d gotten off on a technicality. Maybe I had. My point is that Pinkerton’s story has gotten tangled up over the years with the darker aspects of his agency’s legacy. One of the pleasures of working on this book was finding out more about Allan Pinkerton’s life story, which is more interesting—and far more nuanced—than is generally known. Pinkerton spent his youth marching for the rights of working men in his native Scotland, and came under fire, literally, for doing so. He ran a station on the Underground Railroad, helping fugitive slaves make their way north to freedom. He was a close friend of John Brown, the notorious fire-and-brimstone abolitionist, even though the assistance he gave to Brown in the days leading up to Harpers Ferry put him on the wrong side of the law. Pinkerton even had female detectives working for him, decades before anyone dreamed of putting them on America’s police forces. “I have no hesitation in saying,” he wrote in later years, “that the profession of a detective, for a lady possessing the requisite characteristics, is as useful and honorable employment as can be found in any walk of life.”

Pinkerton was no saint, and I’m not looking to apologize for some of the terrible things that happened on his watch, but there’s a bigger story to be told, and it’s the story of a barefoot cooper who becomes a world-famous detective and makes his bones protecting America’s railroads. One of his biggest clients, I should add, was the Illinois Central Railroad, and the Illinois Central also had a lawyer on retainer whose name was Abraham Lincoln.

Pinkerton was no saint, and I’m not looking to apologize for some of the terrible things that happened on his watch, but there’s a bigger story to be told, and it’s the story of a barefoot cooper who becomes a world-famous detective and makes his bones protecting America’s railroads. One of his biggest clients, I should add, was the Illinois Central Railroad, and the Illinois Central also had a lawyer on retainer whose name was Abraham Lincoln.

And thereby hangs a tale. In fact, it’s the story that Pinkerton himself regarded as the high point of his 30 years in the detective business, and the act for which he wished to be remembered. There’s an inscription on his tombstone that reads: “In the hour of the nation’s peril, he conducted Abraham Lincoln safely through the ranks of treason to the scene of his first inauguration as President.” Sounds like there’s a pretty good book title in there somewhere.

Come find me at the punch bowl, and I’ll tell you all about it.

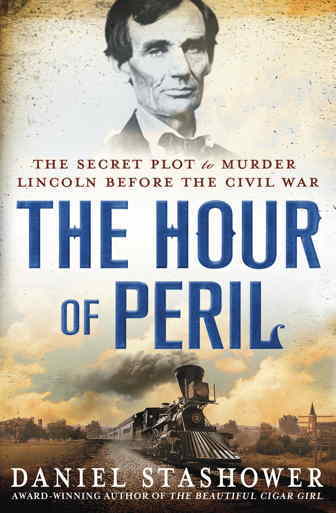

The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War, Daniel Stashower, Minotaur Books, January 2013, $26.99

This article first appeared in Mystery Scene Winter Issue #128.