My Years Writing for Hawaii Five-O

My Years Writing for Hawaii Five-O

Five-0, the elite crime-fighting branch of the Hawaii State Police, does not exist and never did except in the imagination of its creator, Hollywood producer Leonard Freeman, and in the fantasies of his stable of writers. I was one of those writers for six years of my life.

My involvement began in the late 1960s when I got a call from my agent asking me if I would like to write a television script about cops in Hawaii. My first reaction was to say no. Although I had written many TV scripts, I had graduated to the “theeeatre” (pronounce as Bette Davis would), with three produced plays to my credit, including Baker Street, the Sherlock Holmes musical. I felt degraded by the notion that I, a Broadway playwright (as I saw myself), would be reduced to writing cops-and-robbers television.

But I needed the money, so I called the producer.

“I pitched this thing to the network,” Leonard Freeman said on the phone, “and they’ve commissioned six scripts. I want you to come out here and do one of them.”

“Why me?” I asked. “I’ve never been to Hawaii. I wouldn’t be able to visualize it.”

“One question at a time,” he said. “You, because you wrote Baker Street, which tells me you can write mysteries. And don’t worry about having never been to Hawaii. Just write as if it was New York and we’ll change the names of the streets.”

In a few days I was on a plane heading for Los Angeles. I stayed at the Montecito, a haven for visiting New York show people. The guests included Robert Duvall, Yaphet Kotto, and Kheigh Diegh, an Asian-looking man who was really of Egyptian descent. He had played the evil Chinese general in the movie The Manchurian Candidate.

Leonard Freeman, the creator-producer of 5-0, was a short, muscular dynamo who had written for The Untouchables, among other shows. He told me about the trouble he had getting CBS to authorize six scripts of Hawaii 5-0. The TV executives were negative from the start. One of them said, “People who have been to Hawaii have already seen the place. And those who have never been there obviously don’t care. So why should anyone watch this thing?”

Such is the wisdom of the network suits. The original run of Hawaii 5-0 was a record-breaking 12 years, and the reruns will probably go on forever. People all over the world were all saying the McGarrett catchphrase, “Book ‘em, Danno. Murder One.” The very name 5-0 has become synonymous with cops in urban street jargon. All of which proves that when the network executives have a hit, it’s pure accident.

Such is the wisdom of the network suits. The original run of Hawaii 5-0 was a record-breaking 12 years, and the reruns will probably go on forever. People all over the world were all saying the McGarrett catchphrase, “Book ‘em, Danno. Murder One.” The very name 5-0 has become synonymous with cops in urban street jargon. All of which proves that when the network executives have a hit, it’s pure accident.

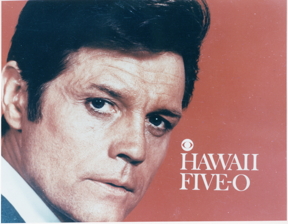

Jack Lord was signed to play Steve McGarrett, the boss of 5-0. In New York, Jack had been a graphic artist who went onstage one night to substitute for a sick friend. After that he took acting lessons at a prestigious drama school where the teacher told him, “You’ll never be an actor; you can only be a star.” He went on to play the lead in the TV series Stoney Burke (about a rodeo rider) and supporting roles in movies including The Billy Mitchell Story and the early James Bond film Dr. No.

With the leading man signed, we were set to roll on the pilot episode, except for one thing: Leonard didn’t have an actor to play the villain, Wo Fat, who was to be McGarrett’s nemesis.

“I got the name Wo Fat from a restaurant in Honolulu,” Leonard said, showing me a matchbook with that very name on it. “He’s going to be a maverick Chinese general who thinks the Chinese government is too soft on America, so he forms his own terrorist group. Who can play a guy like that?”

Once in a while, coincidence comes through. “I’ve got your man,” I said. “He’s at my hotel.” Kheigh Diegh got the role and plagued McGarrett for the next 12 years.

While major roles were played by local professional actors or actors flown in from the mainland, bit parts and extras were recruited right off the streets. Bernie Oseransky would walk through the streets of Honolulu and give out cards to people who looked like possibilities. The card, an invitation to take a screen test, was usually accepted with enthusiasm. If the man or woman passed the screen test, they got a part, sometimes just “Member of Crowd” or “First Gangster.”

Leonard always wanted fresh interesting faces, and there was no lack of them in Hawaii, but sometimes the location staff took shortcuts. Once I was sitting with Leonard at a Los Angeles screening of a new episode. Suddenly, his face became flushed with anger. He shouted across the room to Bob Sweeney, who was the top executive under him.

“If I see the doorman of the Kahala Hilton playing a gangster once more, some people around here are gonna be fired!” he yelled.

I stayed with the show for six years, writing or co-writing 32 episodes. I wrote them in my home on Long Island, and mailed them to CBS in California. This was before the days of fax and e-mail, so if there was a mad rush to have a script in the producer’s hands, I would take the Long Island Railroad to New York City and a taxi from Penn Station to Black Rock (the pet name for the CBS skyscraper in Manhattan). In the basement of Black Rock there was a mailroom where a mail pouch to Los Angeles was dispatched every night. The head of the mailroom, a fellow named Sam, got to know me well.

I would fly out to Hollywood about once a month to get their notes for changes. We would use my visit to discuss new episodes as well. Once I had the notes for revisions, I would fly back home to Long Island and start the process all over. Leonard was a stickler for good episode titles, the kind that grab an audience. Once he had me driving around Los Angeles for an hour trying to come up with a title that was Gothic, foreboding, and suggestive of great wealth. After driving past oil wells, mansions, and strip joints, I came back to his office with a suggestion: “Highest Castle, Deepest Grave.” He loved it. The episode co-starred Herbert Lom and France Nuyen as a father and daughter concealing a murder.

I would fly out to Hollywood about once a month to get their notes for changes. We would use my visit to discuss new episodes as well. Once I had the notes for revisions, I would fly back home to Long Island and start the process all over. Leonard was a stickler for good episode titles, the kind that grab an audience. Once he had me driving around Los Angeles for an hour trying to come up with a title that was Gothic, foreboding, and suggestive of great wealth. After driving past oil wells, mansions, and strip joints, I came back to his office with a suggestion: “Highest Castle, Deepest Grave.” He loved it. The episode co-starred Herbert Lom and France Nuyen as a father and daughter concealing a murder.

During this period, Leonard was having heart trouble. Sometime when I was in California he would ask me to go with him to the doctor’s office, and we would discuss 5-0 story lines on the way, or while sitting in the doctor’s waiting room.

There was an ironbound rule imposed on all the writers: never hand in a script that is more than 54 pages long. For the sake of economy, they didn’t want superfluous material that would later have to be cut. I warned them that my dialogue is terse and usually plays very fast. It didn’t matter to them; 54 pages is what they wanted.

One day I got a phone call from Hawaii. It was Bill Finnegan, who was in charge of production there. “We’ve got an emergency,” Bill said. “We’ve just finished shooting your episode, and the stopwatch tells us we’re a minute short. Can you write a minute of dialogue, and phone it in?” Remember, there were no faxes or e-mail then.

“There’s only one problem,” Bill added. “We’ve torn down all the sets except a telephone booth, so the minute has to be Jack in a phone booth.” I called him back about an hour later with the additional minute...set in a phone booth.

After I had written Hawaii 5-0 for three years, CBS decided it was time for me to visit the islands. As I mentioned before, I had the initial problem of how to visualize a place I’d never seen. I did, however, find a solution. My wife Judy and I had been to Puerto Rico several times on vacations. It occurred to me that Puerto Rico was of a similar size and had a similar climate to Hawaii. From then on, I used Puerto Rico for my visualizations and no one ever knew the difference.

But now, thanks to CBS, I was going to see the real thing. After landing in Hawaii, Judy and I took a taxi to the Kahala Hilton Hotel where CBS had arranged for us to stay. As the taxi pulled away from the airport, I scanned the lush terrain in amazement. “Judy, look!” I said. “Just like Puerto Rico!”

The accommodations at the Kahala Hilton were spectacular. Kahala is an elite residential section, a respectable distance from the tourist mecca of Waikiki. Jack Lord had an apartment near the hotel, and sometimes we would see him jogging on the beach early in the morning.

Jack had a bad reputation with actors. He was an uncompromising perfectionist who demanded that they arrive on the set on time and be letter-perfect in their lines—as he was. Those rules were sometimes ignored by guest stars who partied nonstop from the time they arrived in the islands. If they showed up late on the set with hangovers, not knowing their lines, Jack would berate them in front of the entire cast. They might be stars on Broadway or in Hollywood, but Jack was the king of Hawaii, and no one was allowed to forget it.

Jack had a bad reputation with actors. He was an uncompromising perfectionist who demanded that they arrive on the set on time and be letter-perfect in their lines—as he was. Those rules were sometimes ignored by guest stars who partied nonstop from the time they arrived in the islands. If they showed up late on the set with hangovers, not knowing their lines, Jack would berate them in front of the entire cast. They might be stars on Broadway or in Hollywood, but Jack was the king of Hawaii, and no one was allowed to forget it.

He once fired a permanent cast member for an entirely different reason. The actor made an anti-Semitic remark, which Jack would not tolerate. Ironically, the target of the slur, a public-relations man, was not Jewish.

The trip was a lovely vacation for Judy and me, but useless as far as ideas for the show were concerned. A visit to the Honolulu police department provided no inspiration. I went back to getting my ideas from newspaper articles, my own imagination, and my visions of Puerto Rico.

After returning to Long Island, I got a phone call from Bob Sweeney, a staff producer of the show. I knew from the tone of his voice that something was terribly wrong.

“I have bad news,” he said. “Len was taken to the hospital for heart surgery, and...,” there was a heavy pause, “...he didn’t make it.” It was the beginning of bypass operations, which are now as common as appendectomies. It was hard to imagine Hawaii 5-0 without the creative touch of Leonard Freeman. But the show went on.

Bob Sweeney called me one day thereafter, and said, “We want to do an episode about a traveling circus that comes to Hawaii. We don’t have a story line yet, but we’ve made a deal with a circus that’s in Kansas City right now, and soon they’ll be heading for Honolulu. I want you to leave for Kansas City right away—I’ll meet you there. We’ll absorb the circus atmosphere, meet the performers, and with luck we’ll have a story and a script by the time they get to Hawaii.”

Soon I was on a plane heading for Kansas City, Missouri. CBS had booked an enormous suite at the famous Muehlebach Hotel where U.S. presidents had stayed. The suite was for myself, Bob Sweeney, and Curtis Kenyon, the 5-0 story editor.

After our arrival, Bob sprang his big surprise. “I’m throwing a party for the circus people—all of them—strong men, trapeze artists, clowns, animal trainers, bareback riders, you name it. We’ll have it right here in the suite. There’s plenty of room. I just spoke to the caterers. They’ll be here tomorrow morning with food and booze for 50 people. It’ll be our chance to meet the circus folks, listen to their stories, get to know them as people. Exciting, isn’t it!?”

Reader, hear this advice. If you ever get the urge to throw a big party, don’t do it for circus people. It won’t be the party you’re expecting. Those statuesque sexy women in fishnet stockings who wave at you from the trapeze don’t exist. It’s an illusion. When you see them up close, they are homely females with thick Bulgarian accents, bad skin, uncombed stringy hair, and distinctly alcoholic breaths. And those are the good-looking ones.

Their male counterparts are even worse. They have the added threat of incredible strength, and when strength is mixed with alcohol and underlying belligerence, watch out! Arguments broke out—not with us, but with each other. The arguments turned into fights. Hotel furniture was thrown out of windows. We were afraid that people would be next. Hotel security had to be called, and finally, the police.

“Never again!” Bob said as he dodged an airborne chair. The 5-0 episode was entitled “Presenting in the Center Ring...Murder.” It nearly happened at the Muehlebach Hotel.

Within the framework of its action-adventure format, the show would sometimes make a social statement. An example of this can be found in an episode Iwrote called “Diary of a Gun.” It tracked a handgun through its possession by four different people. In each place the gun was involved in a tragedy or near-tragedy. The idea was avidly approved by Jack Lord, who was a staunch gun-control advocate.

There is a classic anecdote about Jack Lord and guns. One of Jack’s greatest fans was Elvis Presley, who, upon arriving in Hawaii, told his agent to set up a meeting with Jack Lord, his hero. When Elvis came to visit, he merely sat and stared in silence, he was so completely awed. At the end of the visit, Elvis gave Jack a present he had brought—a gold-plated gun. Jack was too much of a gentleman to tell his famous guest what he really thought of guns.

After working on the show for six years, I began to feel written-out. Aside from my own sense of drying up, I felt that the show had deteriorated in the hands of new managerial people. In their attempts to freshen the show up, they added new dimensions to Steve McGarrett’s character. Romantic angles were explored, old girlfriends showed up, that sort of thing. In doing this, they were violating one of Leonard Freeman’s original concepts. He had often told me, “I don’t want to know anything about McGarrett’s personal life. He exists only as a cop.” Leonard was right. Delving into McGarrett’s psyche gave the show a soap opera tinge. The original impact was compromised.

So now I watch the reruns occasionally, and when I catch one of my episodes, I get a nostalgic feeling, but unfortunately no money. Our contracts back then provided residuals for only ten runs, and we are long past that mark.

How did the networks get away with that? Book ‘em, Danno. Larceny One.

Jerome Coopersmith is known for his television work on Hawaii Five-O (1968), 'Twas the Night Before Christmas (1974), and Armstrong Circle Theatre (1950). He is also a playwright and was nominated for Broadway's 1965 Tony Award as Best Author (Musical) for Baker Street.

This article first appeared in Mystery Scene Spring Issue #84.