Take It to the Bridge

Take It to the Bridge

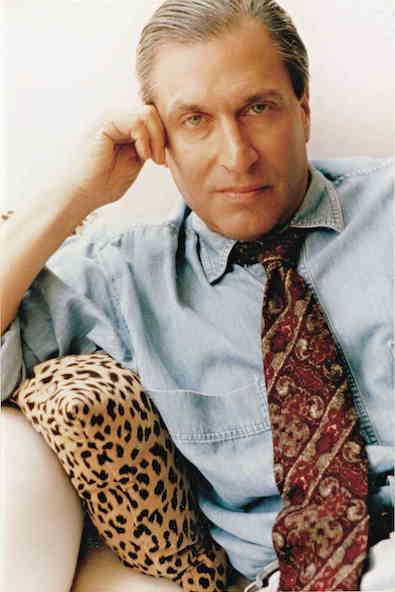

Nicholas Meyer’s work as a novelist, screenwriter, and director is a testament to the power of popular art to entertain, illuminate, and—on occasion—affect the course of history. He’s taken audiences from Victorian England (The Seven-Per-Cent Solution) to the 23rd century (Star Trek II, IV, and VI) to the end of the world as we know it (The Day After). A firm believer in story and character, he upholds these virtues in an industry that prides itself on spectacle and stereotype.

Meyer’s own story began in New York City on Christmas Eve, 1945. The son of psychiatrist and author Bernard C. Meyer and concert pianist Elly Kassman, he was raised in comfort on the Upper East Side. Meyer was one of those children who are motivated by interest and not by discipline. School was a trial and a chore. Jules Verne, Alexandre Dumas, Classics Illustrated comic books, and late-night movies provided his real education.

After graduating from the University of Iowa, he worked as a publicist for Paramount Pictures, then moved to Los Angeles in the early ’70s to pursue a career as a screenwriter. Early efforts included the TV movies Judge Dee and the Monastery Murders (1974) and The Night That Panicked America (1975, co-written with Anthony Wilson). Dee was an adaptation of one of Robert van Gulik’s mysteries about a real-life Tang dynasty circuit court judge. Night was a retelling of the havoc created by Orson Welles’ 1938 “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast. Both scripts reveal Meyer’s penchant for stories set in the past that involve historic characters—a proclivity that would bring him his first major success.

The Writers Guild of America went on strike in 1973. As Meyer writes in his memoir The View From the Bridge, he finally had the opportunity to start:

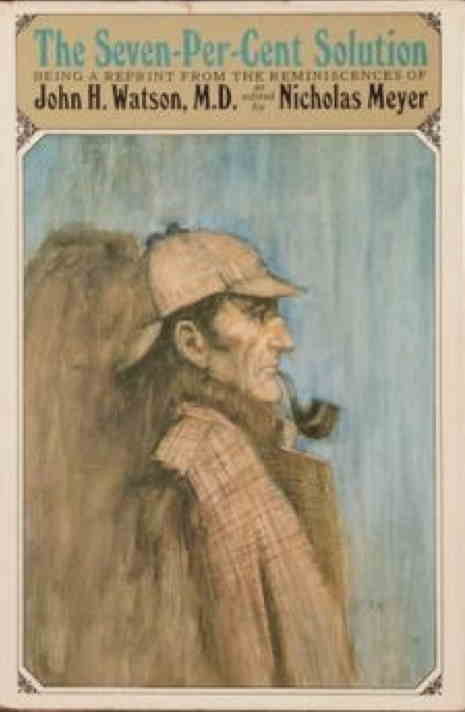

...banging away at my long-gestating notion of a Doyle pastiche in which Sherlock Holmes met, matched wits with, and finally collaborated with Dr. Sigmund Freud. Freud cures Holmes’ cocaine addiction; in return, Holmes’ methodology sets Freud on the analytic path that will lead to psychoanalysis.

That notion became The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1974). The novel was a best seller and was made into a film two years later. Meyer’s screenplay garnered an Academy Award nomination.

Not content to merely put Holmes and Watson through their paces, Meyer reexamined the very basis of their world. Far from being “the Napoleon of Crime,” Professor Moriarty is a victim of Holmes’ cocaine-induced paranoia. He’s also the reason for the kinks in Holmes’ psychology. The great detective’s misogyny, as well as his single-minded crusade against crime, stem from Moriarty’s involvement in Holmes’ childhood.

Not content to merely put Holmes and Watson through their paces, Meyer reexamined the very basis of their world. Far from being “the Napoleon of Crime,” Professor Moriarty is a victim of Holmes’ cocaine-induced paranoia. He’s also the reason for the kinks in Holmes’ psychology. The great detective’s misogyny, as well as his single-minded crusade against crime, stem from Moriarty’s involvement in Holmes’ childhood.

Two sequels followed. The West End Horror (1976) is set in Victorian London’s theatre world and peopled with such luminaries as George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, Bram Stoker, and Gilbert and Sullivan. A copy of Romeo and Juliet provides a dying clue to a secret that could destroy England, if not the Continent itself. Horror is a better-constructed book than its predecessor. Solution divides into two enjoyable halves—Holmes’ cure and the case that followed—whereas Horror’s story is all of a piece. Meyer is justifiably proud of his achievement.

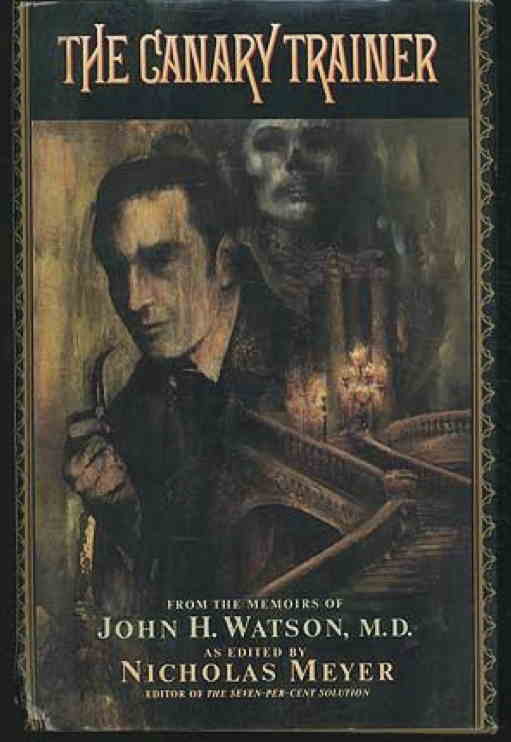

The Canary Trainer (1993) takes place during the period of Holmes’ peregrinations through Europe after his “death” at Reichenbach Falls. Employed as a violinist in the orchestra of the Paris Opera, Holmes must grapple with the ghostlike figure who haunts the building’s vast and gloomy underground. Meyer’s third pastiche builds to an explosive ending, thanks to dynamite belonging to the builders of the Paris Metro.

Negotiations with the Conan Doyle estate for the use of the Holmes and Watson characters dragged on for so long that Meyer wrote another book while waiting for Solution to be cleared for publication: Target Practice (1974).

Meyer has called the book a Ross Macdonald pastiche. Target Practice’s first-person narration owes something to Lew Archer’s wearily sympathetic tone. More importantly, Meyer shares with Macdonald a sense of how private torment and public events are intertwined. For Macdonald’s characters, the public event was often World War II. For the characters in Target Practice, it’s Viet Nam.

Sergeant Harold Rollins III, accused of collaborating with the enemy while being held in a North Korean P.O.W. camp, has committed suicide. His sister Shelly suspects he may not have killed himself and wants him posthumously cleared of the charges. She hires private detective Mark Brill to investigate. Brill is a middle-aged widower, an ex-cop and ex-military man who uses his job as a screen between himself and the rest of the world. The case takes him from Los Angeles to the East Coast and the Midwest before the skein of incest and murder is untangled and another death occurs. Target Practice was deservedly nominated for a Best First Novel Edgar. (It lost to Gregory Mcdonald’s Fletch.)

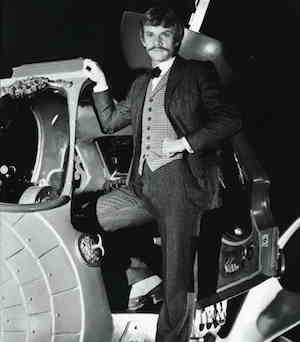

Meyer debuted as a film director with Time After Time (1979). He also wrote the screenplay, which was based on a novel by University of Iowa classmate Karl Alexander. In the film H.G. Wells doesn’t just write about time machines, he’s actually invented one. It’s stolen by a doctor acquaintance who is, in fact, Jack the Ripper. Jack finds himself in 20th-century San Francisco, where the chaos and violence of the modern world strike him as tonic. Wells (played by Malcolm MacDowell, see photo on left) follows the Ripper to the city by the bay and attempts to bring him back to the 19th century and justice. It’s a gem of a film, moving and sometimes terrifying.

Meyer debuted as a film director with Time After Time (1979). He also wrote the screenplay, which was based on a novel by University of Iowa classmate Karl Alexander. In the film H.G. Wells doesn’t just write about time machines, he’s actually invented one. It’s stolen by a doctor acquaintance who is, in fact, Jack the Ripper. Jack finds himself in 20th-century San Francisco, where the chaos and violence of the modern world strike him as tonic. Wells (played by Malcolm MacDowell, see photo on left) follows the Ripper to the city by the bay and attempts to bring him back to the 19th century and justice. It’s a gem of a film, moving and sometimes terrifying.

His biggest challenge—and proudest accomplishment—as a director was the TV movie The Day After (1983). What if the unthinkable happened and a nuclear war took place? Edward Hume’s script followed a handful of characters in Lawrence, Kansas, and environs before and after a nuclear strike. The devastation is immense. All is “changed, changed utterly,” in Yeats’ words, and for the very worst.

Filming was a massive undertaking not made easier by a skittish network, and the finished product was attacked by conservative pundits and apologists such as William F. Buckley and Henry Kissinger. It’s estimated that over a 100 million people watched The Day After when it was broadcast on the evening of November 20, 1983. President Ronald Reagan saw the film before its ABC showing. His belief that a nuclear war could be won was changed by The Day After. Reagan claimed the movie contributed to his signing of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 1987. If one has doubts about the ability of art to affect the world at large, one need only point to The Day After.

Meyer is perhaps best known as the man who saved Star Trek (and killed Spock in the process). For the lowdown on his involvement as a writer and/or director on three of the original-cast films, seek out The View From the Bridge: Memories of Star Trek and a Life in Hollywood (2009). The Trek devotee will not be disappointed and neither will the more casual reader. Bridge is as thoughtful and outspoken as its author. Meyer is as quick to tell you about his flaws and failures as he is of his successes. Bridge’s only flaw is that it isn’t longer.

Meyer’s novel Confessions of a Homing Pigeon (1981) isn’t a mystery, though it deals with the biggest mysteries of all: love and loss, life and death. When young George Bernini’s trapeze artist parents die in a circus accident, he’s sent to postwar Paris to live with his Uncle Fritz, an eccentric composer and pianist. Their adventures together are wild and winning but come to an abrupt end when Fritz loses custody of the child to an aunt in Chicago. George is dropped into the heart of Eisenhower’s America. A most unhappy fish out of water, he dreams of nothing but returning to France. But how is he going to do it?

Meyer’s novel Confessions of a Homing Pigeon (1981) isn’t a mystery, though it deals with the biggest mysteries of all: love and loss, life and death. When young George Bernini’s trapeze artist parents die in a circus accident, he’s sent to postwar Paris to live with his Uncle Fritz, an eccentric composer and pianist. Their adventures together are wild and winning but come to an abrupt end when Fritz loses custody of the child to an aunt in Chicago. George is dropped into the heart of Eisenhower’s America. A most unhappy fish out of water, he dreams of nothing but returning to France. But how is he going to do it?

It’s clear that Confessions draws on the circumstances of Meyer’s life. A checkered school career, the power of art to soothe and save, the death of a loved one from cancer are part and parcel of Meyer’s experience—and that of others.

I’m one of those others. I’ve loved Confessions since I first saw it on the new-arrivals shelf in a small-town library in Minnesota and took it home. It’s my favorite of Meyer’s books, and a copy of it rests on the desk beside me as I type these words, all these many homes later.

Nicholas Meyer is alive and well and working in Los Angeles. I can’t wait to see what he does next.

Joseph Goodrich is the author of the Edgar-winning play Panic and the editor of Blood Relations: The Selected Letters of Ellery Queen, 1947–1950. He lives in New York City.

This article first appeared in Mystery Scene Summer Issue #130.